Shaping the Future of Demonstrative Evidence Animation

New techniques that save money, enhance damage awards

By Peder Rudling

Confuse vs. Clarify – When Animation Becomes a Critical Tool for Winning your Case

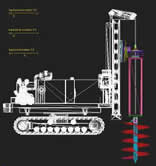

One approach that defense attorneys often favor is the art of confusion. I was recently involved in a construction accident case, where the machine involved was so complicated that words just weren’t enough to explain how it operated.

If a juror did not understand how this machine works – how could plaintiff’s counsel hope to explain how his client was wronged by the defendants?

The answer was found in using animation.

After creating a detailed animated replica of the machine in question, demonstrating its operation and purpose, followed by a reconstruction of the accident seen from both front and top perspectives, my client’s argument became evident to everyone.

The opposing counsel deposed me for 5-1/2 hours in an attempt to find some technicality based upon which to dismiss the animation, but eventually settled, rather than face the prospect of a jury’s punitive damage award.

Differences in Admissibility Standards

There is a difference between the types of animation acceptable for mediation vs. that acceptable for jury trials. You can be far more argumentative and subjective when creating animations for mediation. There is a vast library of tools available to articulate your client’s position, and the effective demonstrative animator will maintain continuous situational awareness of which tool is appropriate for any given case.

Examples of subjective tools include sound effects (bone crunching, crashing, screeching tires), facial character animation (horror, fear, pain), and dramatic lighting or camera angles.

Animations for trial require a more neutral approach. You will demonstrate your expert’s opinion by meticulously reconstructing conditions at the time of the accident, animating only actual viewpoints of witnesses, and animating “inside” video or still photographs of the accident scene.

It’s important to maintain a modular approach to your animation, so that you can quickly convert it from mediation to trial use.

Focus on the Human Factor – Invoke Sympathy for your Client

When creating an accident reconstruction animation for a plaintiff, try to put the viewer in the shoes of your client.

Make the viewer think about how it must have felt to be violently pulled into that factory machine. Try to convey the emotion felt during the final moments of the deceased, just when he realized that he is about to be crushed by a semi.

Show the unfairness or negligence by the defendant that led to the irrevocable brutal demise.

To master the art of the storytelling is to find a persuasive, yet admissible way to connect with the viewer’s emotions.

An angry, empathetic jury can lead to a very favorable damage award or settlement.

Alternate Scenarios

A highly effective strategy often used by animators is to portray a “what-if” scenario of how an accident could have been prevented.

For example, by demonstrating how a relatively inexpensive safety measure was skipped at the expense of your client’s safety, an animation can make a tremendous impact in revealing negligence and resulting in a large punitive verdict.

Animation – So Versatile

Multiple viewing angles, slow motion, see-through illustrations, even bringing a dead person to life in an accident reconstruction are some of the unique advantages animation brings to the table.

The only limitation of its use is the imagination and creative skill of the animator.

Focus on the Core of the Argument

The demonstrative animation must absolutely make a successful point for your client. A beautifully created, feature-film style animation which fails to convey your client’s argument is ultimately worthless. It may be useful for your demo reel, but that’s about it.

Avoid Events Not in Dispute

Unless you have good reason to do so, avoid animating events not in dispute by either party, because to do so may create an opportunity for opposing counsel to dig up some technicality which could hurt the admissibility of the animation entirely.

This strategy is also a great technique to save your client’s money, because the dynamics and details involved with the recreation of the impact and post-impact is what take the most time for the accident reconstruction animator.

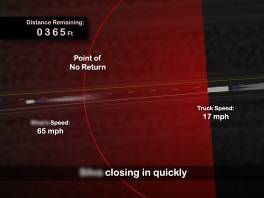

Using a freeway car accident as an example, you may choose to only animate the events that lead up to the accident and stop on a freeze frame at the precise moment of impact, followed by a slide show of accident scene photographs.

This way you have chosen to address only the contested points of the argument while carefully avoiding the Pandora’s Box of non-contested events.

Integrating Animation with Video, Photographs

Quite often you will have a wealth of photographs at your disposal as part of the case materials on which you will base your animation work. The skilled animator can often use these photographs with the animation itself, which yields significant benefits.

Integrating established photographic or video evidence boosts the credibility of your work. For example, using an accident scene photograph of the intersection where a pedestrian was hit by a car, then adding an accident reconstruction animation inside that photograph yields a persuasive piece of evidence that gives the viewer a sense of being a witness to the event itself.

It is also more efficient to model only the minimum virtual geometry needed to integrate with the photograph, rather than to model the entire virtual environment from nothing. The cost-to-benefit ratio of this technique is significant and can be the deciding factor to a client who is arguing a smaller damage dispute.

The Use of Sound Effects

Any plaintiff lawyer would likely agree that enhanced juror sympathy is linked to higher damage awards. I don’t know why, but for some reason courtroom animations have been silent until recently.

Consider this -- Watching an animation of a person slip and fall is only moderately effective. However, simply adding the sound of a femur snap and a person’s scream will make a juror jump.

The emotional impact of realistic and relevant audio information ought to be considered at least as relevant as the visual information.

Maintain clear notes

Keep records of all your scripts and calculations. For example, you should be able to explain to anyone why the tire rotation of your vehicle is accurate, based on its diameter and the speed of the vehicle. You should be able to look up what lenses you selected for your cameras or be able to point to a graph on which you based the GPS location of your animated vehicle.

As a demonstrative evidence animation specialist, there is always a possibility that you may get deposed. Unless you maintain clear records of how you arrived at your animation, you may have a problem establishing the credibility and accuracy of your work.

Most of the time however, clear notes come in handy when revisiting a project you haven’t worked on in a while. Trying to memorize all the details of your animations is just not practical.

Your expert’s written statements, charts, and opinion is your friend. Police reports are useful also, but they are often less accurate than, and should generally defer to the opinion of an accident reconstructionist and/or human factors expert, at least as far as what you base your animation upon.

Know your Role as a Demonstrative Evidence Animation Specialist

As a demonstrative evidence animation specialist, you are simply a translator conveying technical concepts to a non-technical audience. Be aware that your work does not represent your own opinion, but is rather the visual representation of someone else’s opinion -- the expert witness. Make sure you clearly understand and address every point your expert is trying to get across.

The relationship between the animator and the expert is a partnership that should be nurtured. If your work is not precisely in sync with his or her opinion, your animation is at risk of being useless or even harmful to your client.